White paper

Introducing UX Evals

Jan 22, 2026

—

Christopher Monnier

UX Evals: A New Methodology

A new methodology for the age of AI to better evaluate non-deterministic user experiences.

Why traditional methods were falling short

Sometime last year, a few of us on the Copilot team at Microsoft AI had a similar feeling: our eval metrics didn’t feel aligned with our experience using the product ourselves. Something felt off.

So we began doing what we always do – talking to people about how they use our product. What did they think about the quality of our responses? How did it compare to competitors? What would they like to see in a response that they weren’t yet seeing?

After these conversations, it became clear that our existing suite of evals weren’t enough to capture the nuances, diversity, and complexity of the experiences users were having with our product. We needed a way for users to tell us directly about their experiences, and since each user’s experience with the product is different, we needed to do this at scale.

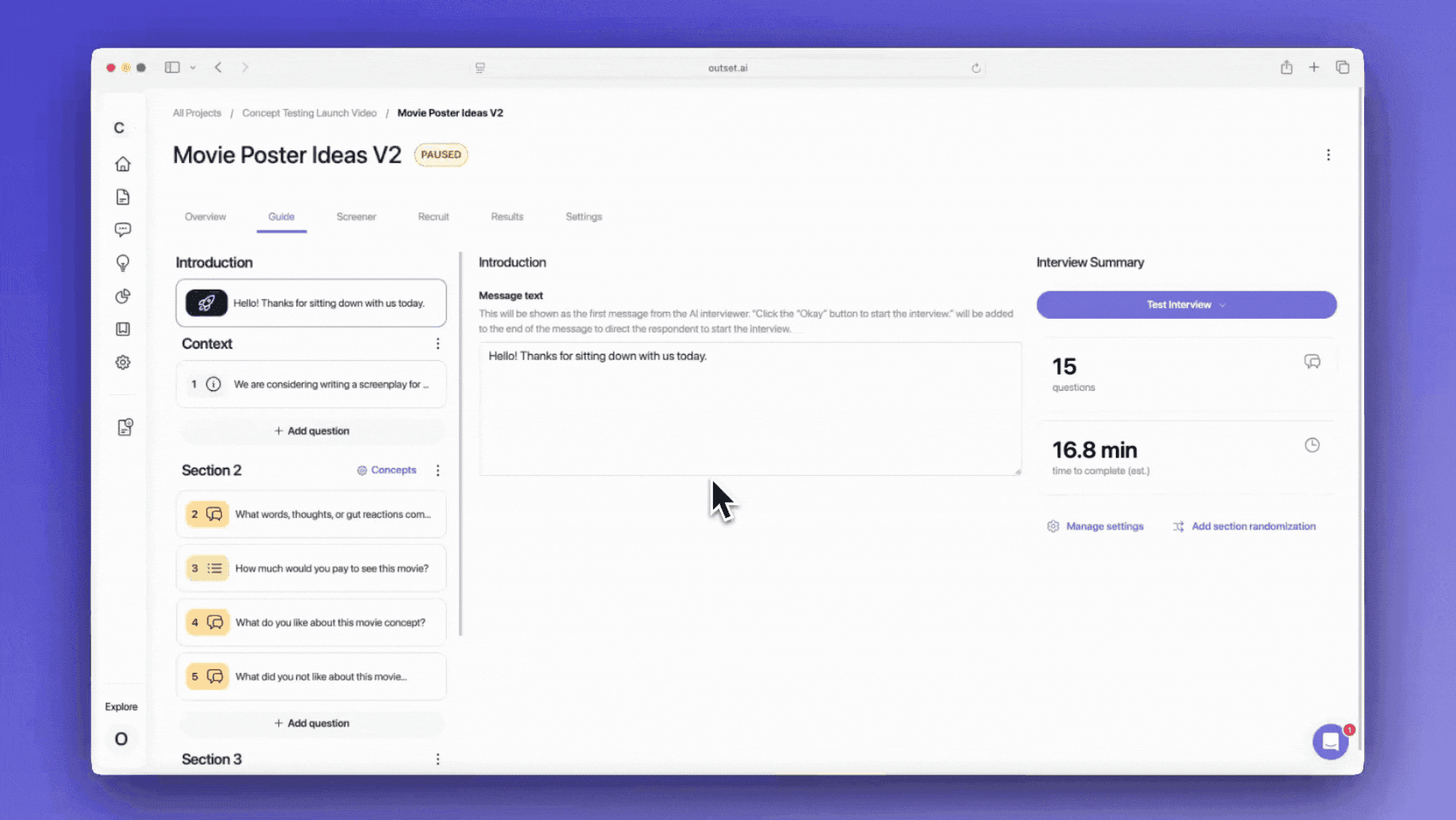

At the same time, we were working with Aaron’s team at Outset to ramp up our usage of Outset’s AI-moderated research tool. After a few quick pilot studies, we realized we’d be able to leverage an AI-moderator to run dynamic interviews blending qual and quant at scale.

As we scaled our usage and saw the results, we realized this new methodology – UX Evals – has utility beyond our team and beyond the world of AI model companies. Every product is quickly becoming an AI product, and this methodology is helpful anytime researchers want to understand how useful their product is in the real world.

From pixels to tokens

UX research grew as a key role in any product org for a very specific reason: to make sure human perspectives were present in decision making.

For decades, this work played out in a world of pixels, screens, and flows, where deterministic user experiences varied little between users. So even as successive waves of technology ushered in the web, social media, and mobile, UX researchers could apply a relatively standard toolkit of methods to observe behavior and surface friction, then reliably advocate for human needs.

But AI flips this paradigm on its head. Today’s most important user experiences are dynamic, probabilistic, and conversational, unfolding in an infinite number of ways that are different for each user. AI-powered experiences adapt depending on the context and intent of each user, resulting in unique permutations of everything from phrasing and tone to the user interface itself.

In short: today’s most important products are built on tokens, not pixels.

And yet, the way we evaluate those experiences has not kept pace.

Across the industry, teams are shipping AI that performs well in internal evaluations, clears benchmarks, and passes launch gates — but still leaves users confused, mistrustful, and unsatisfied.

This gap exists not because teams have deprioritized UX, but because the methods that once worked so well were designed for products where every user has a different experience.

To close that gap, UX research needs to evolve.

The limits of traditional UX research

Since traditional user experiences varied little from user to user, qualitative research with a small number of participants was very effective at surfacing issues and helping product teams iterate from rough concepts to finished designs.

AI experiences fundamentally break those assumptions.

When the interface is a conversation, there is no single path through the experience. Users may reach the same goal via radically different routes, the system behaves probabilistically, and value often emerges only after multiple turns — sometimes through confusion, repair, or reframing.

Traditional UX methods still play an essential role. Generative research, diary studies, and in-depth interviews are critical for understanding user needs, mental models, and expectations. But when it comes to evaluating how well an AI system performs in practice, these methods encounter structural limits.

They are difficult to scale. They are hard to compare across versions or competitors. And they struggle to produce reliable signals, particularly for AI-based products where relatively simple system prompt changes can dramatically alter a product’s user experience.

This doesn’t make UX research obsolete — in fact, it means the job of the UX researcher is even more critical.

And harder.

The limits of traditional AI evals

On the other hand, AI teams recognized early that conversational systems demanded new forms of evaluation. A cottage industry of evals emerged, with two broad categories: machine evals, where one LLM judges the output quality of another, and human evals, where human experts judge output quality.

These approaches have clearly delivered enormous value, but they also encode a set of assumptions that increasingly diverge from real-world use.

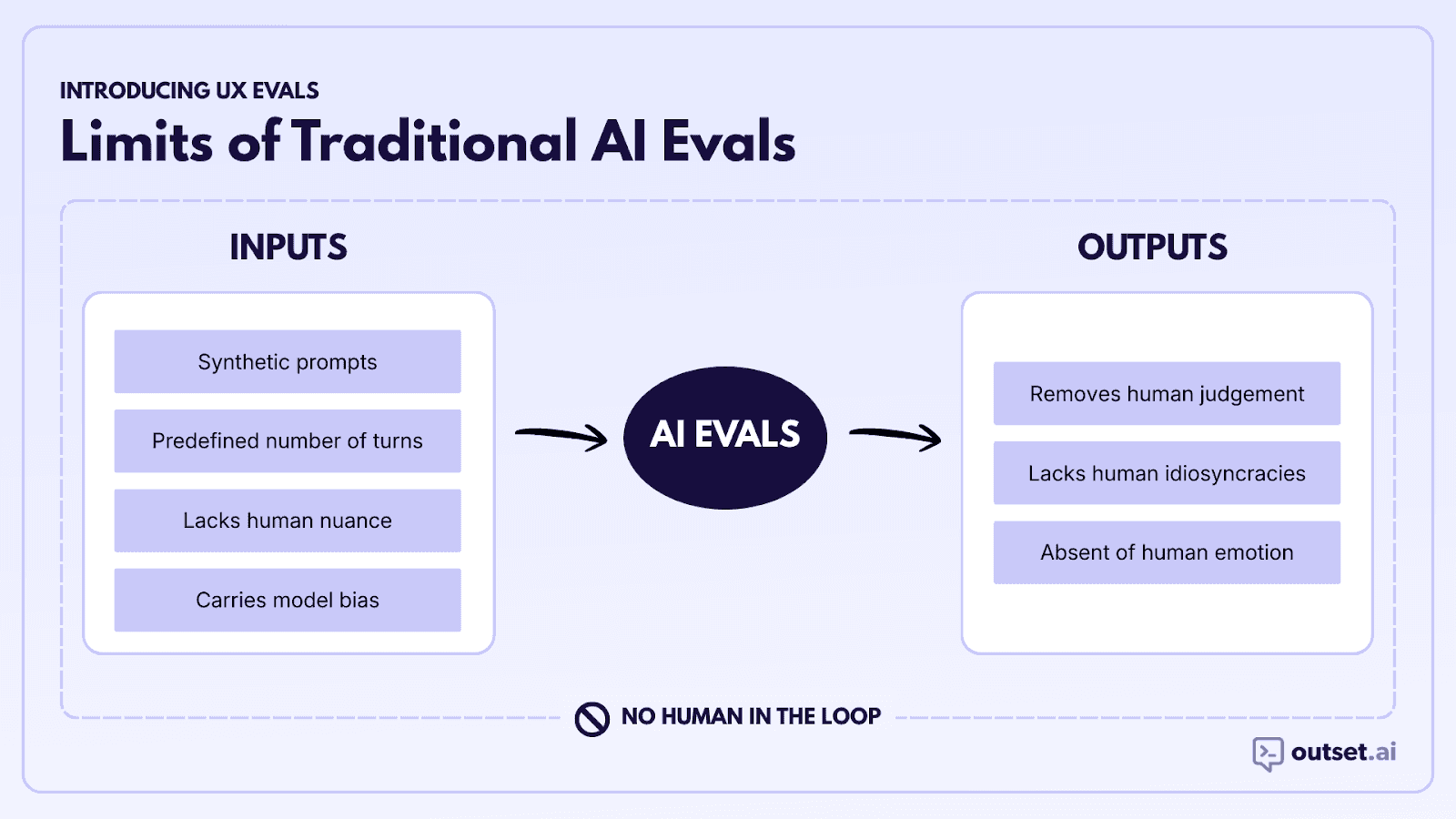

Consider the inputs and outputs that go into an eval:

In most evals, the inputs are typically a series of synthetically-generated conversations that fail to capture the nuances of human input. The prompts are too well-constructed (most humans are not great at prompting), they often consist of a predefined number of turns, and they carry with them whatever biases are built into the model that was used to generate them.

Eval outputs have similar issues. The LLMs used in machine evals don’t have feelings, they’re not worried about something happening tomorrow, they’re not preoccupied with the dating lives of celebrities, etc. These things can be simulated, of course, but they’re not nearly as idiosyncratic as actual humans.

And even the outputs of traditional human evals have issues, as most human evals are performed by third-party judges who, even with a high degree of empathy, can never truly internalize the dreams, fears, and goals of a human having a conversation.

There is a fundamental tradeoff happening in these evals: sacrificing human idiosyncrasy for eval simplicity.

This makes sense when model designers want to quickly iterate and see if they’re on the right track. But if you’re only doing machine evals and third-party human evals, you’re missing a key perspective – the users themselves!

Enter: UX Evals

UX Evals are a category of AI evaluation grounded in user experience research. They’re the next step in a long history of methods for benchmarking user experiences such as SUS (System Usability Scale), CSAT (Customer Satisfaction), and PMF (Product-Market Fit). Like these earlier techniques, UX Evals aim first and foremost to understand whether a user experience delivers value to the person using it.

Specifically, UX Evals are a technique for evaluating AI systems through first-person, multi-turn interactions with regular people at scale. Participants bring their own goals, context, and questions. They engage with the system the way they would in real life — imperfect prompts, shifting intent, moments of uncertainty included.

Crucially, the person who has the conversation is also the one who evaluates it.

This reframes evaluation from an external judgment to an experiential one. The signal comes from lived use, not proxy measures.

UX Evals don’t necessarily replace benchmarks or traditional UX methods. They leverage AI-moderated research capabilities to sit alongside them, encoding large scale qualitative insight into model iteration and product development.

How we conduct UX Evals

Our UX Evals mirror how AI is actually used in the wild. Crucially, UX evals are first-person, which has two key benefits:

The messiness or real life is captured in the inputs.

The person who had the conversation judges whether the output delivers value.

Step 1

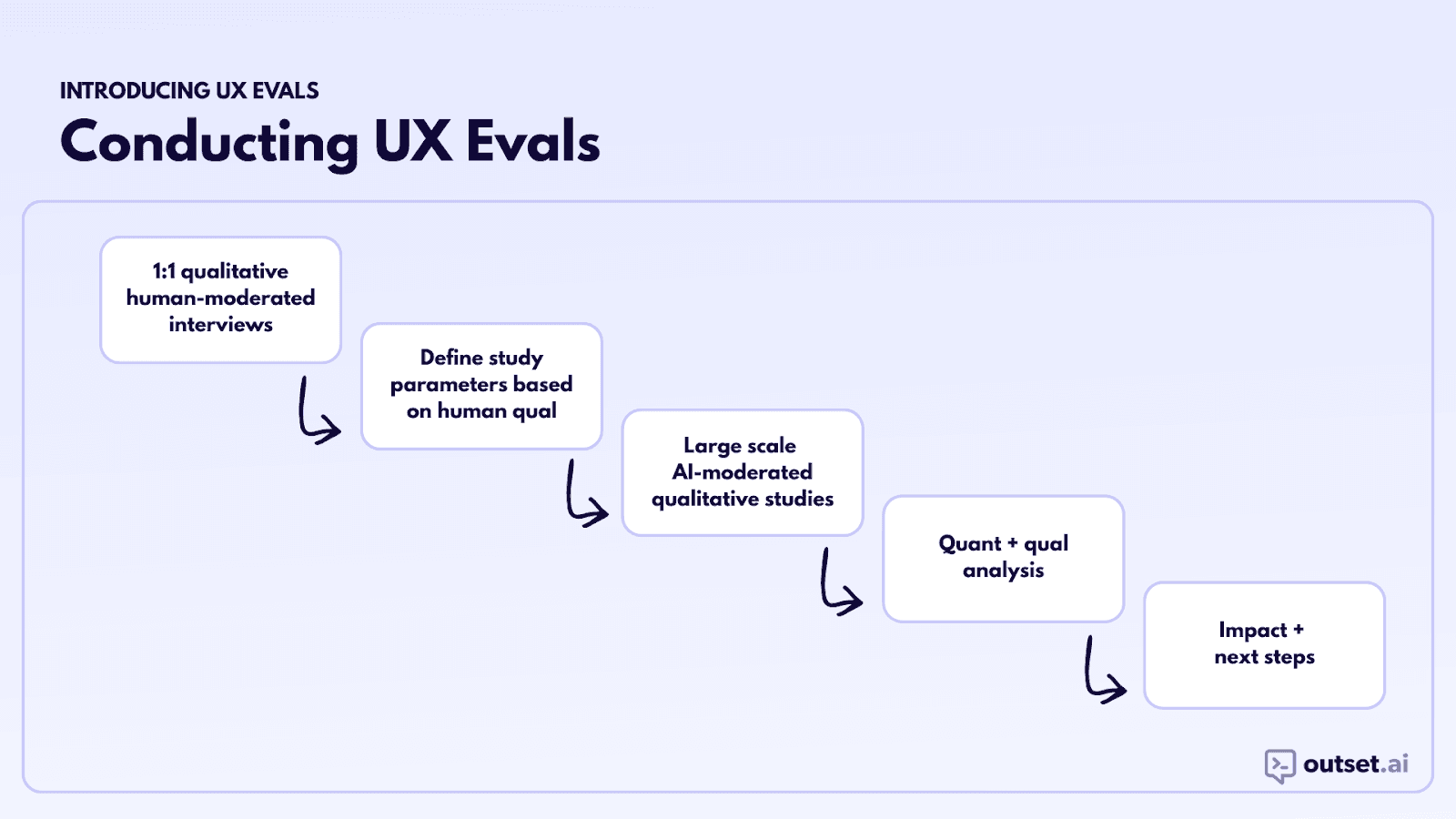

We start with qualitative research to identify the dimensions of the experience that seem to matter most to users. We do this through regular qualitative research, i.e. 1:1 human-moderated interviews. The skills UX researchers have sharpened are essential here – navigating ambiguous interviews, going off-script when needed, synthesizing disparate datapoints.

Step 2

Choose specific demographic characteristics and add screeners to find people exhibiting particular behaviors (e.g. heavy AI users) or in particular situations (e.g. stay-at-home parents).

Step 3

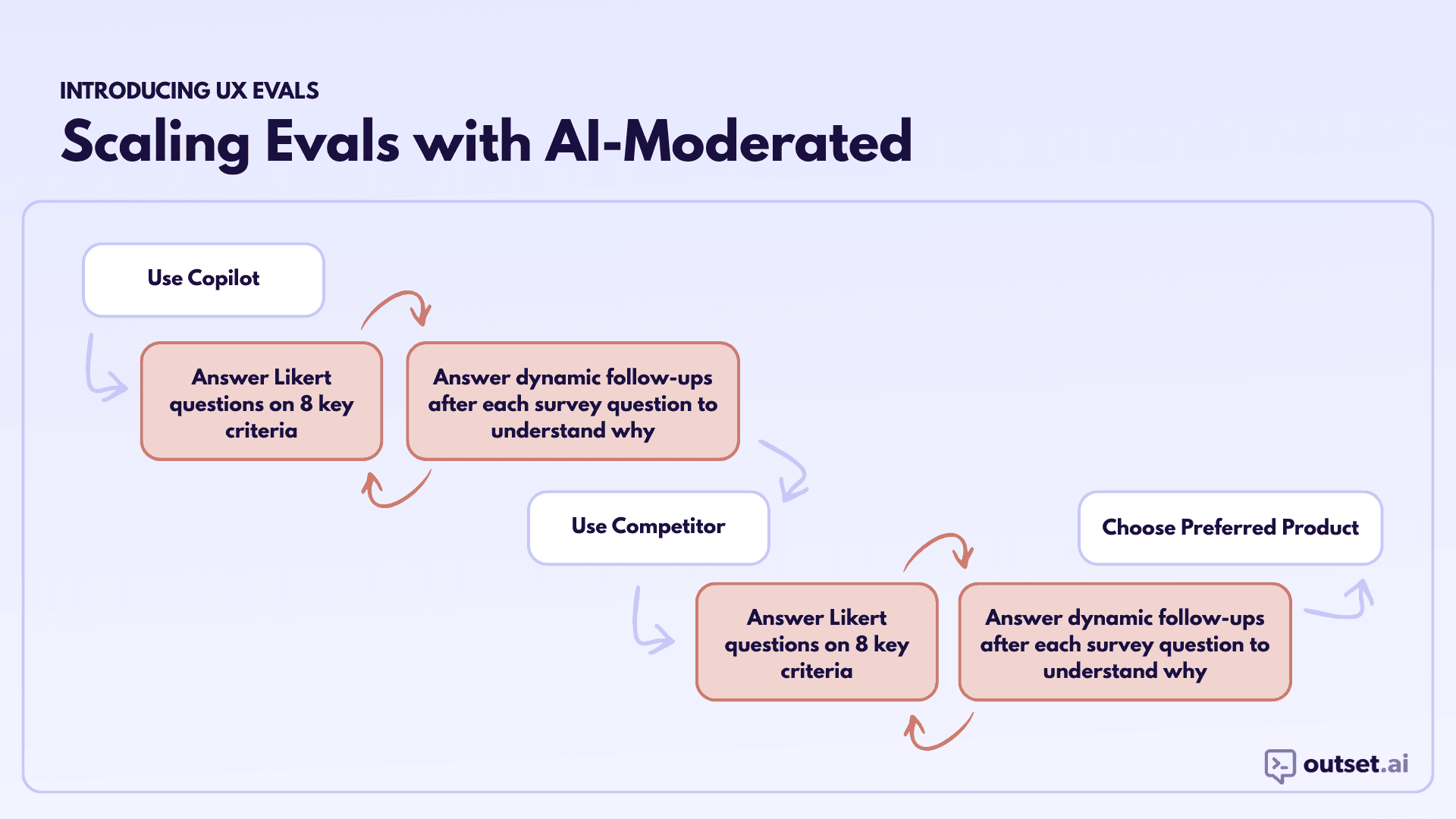

Once we have the 8-12 dimensions we feel confident about, we’re ready to scale the eval with AI-moderated interviews. We typically design a study with two different products. It could be two different versions of our own product or our own product and a competitor’s. Participants try each product in a counterbalanced order, rate each along various dimensions, and use AI-moderated interviews to understand the why behind each rating. Here’s the process in more detail:

Ask participants to have a conversation that falls into a broad-based category: Since AI-driven experiences inherently include so much variability, it’s important to contain the eval to a particular topic or category. We avoid scripted prompts or tightly constrained tasks, and instead ask participants to, for a given category, engage with the product the way they would in real life, which means:

They decide what they want to accomplish

They phrase messages and questions in their own imperfect way

They use the product as much or as little as they see fit

Ask quantitative survey questions with qualitative follow-ups: After interacting with each product, we ask participants to rate their experience along a series of dimensions using Likert scales presented in a randomized order. These dimensions are rooted in a qualitative understanding of what matters to users and should be things that the users themselves are uniquely suited to evaluate. Some examples include:

Usefulness

Trust

Clarity

Helpfulness

Ask participants to choose their preferred experience: After participants have tried both products and rated their experience with each, we ask them to choose the one they preferred.

Step 4

We collect enough data to make statistically-significant analysis possible and then analyze the results to compare each product along the various dimensions, relative differences between the two products, and identify which dimensions drive product preference.

What really makes this method powerful is the ability to marry the quantitative analysis described above with rich qualitative insights, which we get through screen recordings, dynamic follow-up questions, and example transcripts. This allows us to understand not only which dimensions of the experience matter most, but also to unpack why this is and in turn make meaningful changes to the product experience.

Read more about how to conduct them here.

Real-world applications

UX Evals matter anywhere AI behavior shapes the user experience — not just in organizations building foundation models.

As AI becomes embedded across products, more teams are responsible for experiences that are conversational, adaptive, and probabilistic by default, whether it’s a support interaction, a recommendation flow, a planning assistant, or even a voice agent (no pixels to test at all!).

More broadly, UX Evals should be leveraged for any product where...

The experience unfolds over multiple turns or interactions

User intent is ambiguous or evolves over time

The system plays a role in decisions, judgment, or sensemaking

Trust, tone, and clarity matter as much as correctness

In all of these contexts, success cannot be measured solely by whether the system produces a correct response. It must be measured by whether the interaction helped a real person move forward.

What this means for the future

AI-native products are becoming the default.

In that world, teams that rely solely on benchmarks or legacy usability methods will have a critical blindspot: the lived experiences of their own users.

UX Evals represent a shift:

From pixel-based experiences to tokens-based ones

From assuming what users want to listening to what they care about

From simple win-rates to rich results

The question isn’t whether this shift it’s coming, it’s how well teams adapt. And as UX research continues to evolve, methods like UX Evals won’t be optional — they’ll be foundational.

Credits and acknowledgements

This method is the result of a collaboration with Chuck Kwong, Wendy Wang, and Jess Holbrook. We co-developed this method and have continued iterating and refining the approach. Specifically, Chuck pioneered the quantitative analysis required to identify drivers, Wendy spearheaded the process for gathering and analyzing qualitative feedback, and Jess provided leadership on the approach and scaling this methodology with senior leaders.

About the author

Christopher Monnier

Principal UX Researcher, Microsoft Copilot

Chris Monnier is a Principal UX Researcher on the Microsoft Copilot team where him and his team are redefining how we understand users in the new AI era. With an esteemed background at companies like Airbnb and Opendoor prior to Microsoft, Chris brings a true curiosity to research and loves helping builders figure out the world.

Interested in learning more? Book a personalized demo today!

Book Demo